Musings |

|

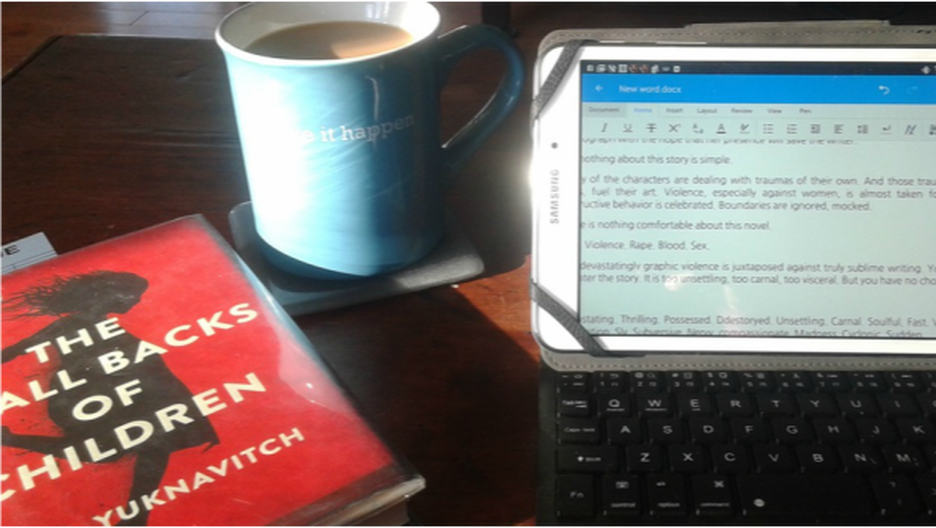

Most novels allow you to know how you feel about them while you're still reading, or at least as soon as you finish that last page. The Small Backs of Children by Lidia Yuknavitch is nothing like most novels. This is a book that makes you work. The story seems simple enough. A photographer captures an award-winning image of a young Eastern European girl running towards the camera, fleeing an explosion that has killed her family and destroyed her home. The photograph haunts an American writer, who ultimately falls into a deep depression as her own losses and the haunting image overwhelm her ability to function in the world. Her friends, all artists, concoct a crazy plan to rescue the girl in the photograph with the hope that her presence will save the writer.

But nothing about this story is simple. Many of the characters are dealing with traumas of their own and they inflict trauma on one another. And those traumas, in very real ways, fuel their art. Violence, especially against women, is almost taken for granted. Self-destructive behavior is celebrated. Boundaries are ignored, mocked. There is nothing comfortable about this novel. War. Violence. Rape. Blood. Sex. The graphic violence is juxtaposed against truly sublime writing. You may not want to enter the story. It is too unsettling, too carnal, too visceral. But you have no choice. Yuknavitch bewitches the reader. The novel moves so quickly that it’s hard to get your bearings. When you finally come to the end, and are allowed to reenter the world, it feels as if you are coming out of a trance. It feels as if you’ve been a part of a subversive movement; that you are privy to information that is dangerous; that you know more than you should. And perhaps that is true. I know artists who talk about their pain fueling their art, who can almost detach from a truly terrible experience so they can observe it even as they are experiencing it. A playwright friend talks about composting her experiences, turning each one into rich soil from which to grow her plays and scripts. Another friend, an artist and critic, considers such experiences absolutely essential for art. Can a person whose life has been simple, golden and uncomplicated, make good art? Or is pain a necessary part of art? And where is the tipping point? And why is it that pain and trauma is so important to the creative life? Or is this just the romantic story we tell?

1 Comment

|

|

|

The Scribbler's Journal

|

Contact |