Musings |

|

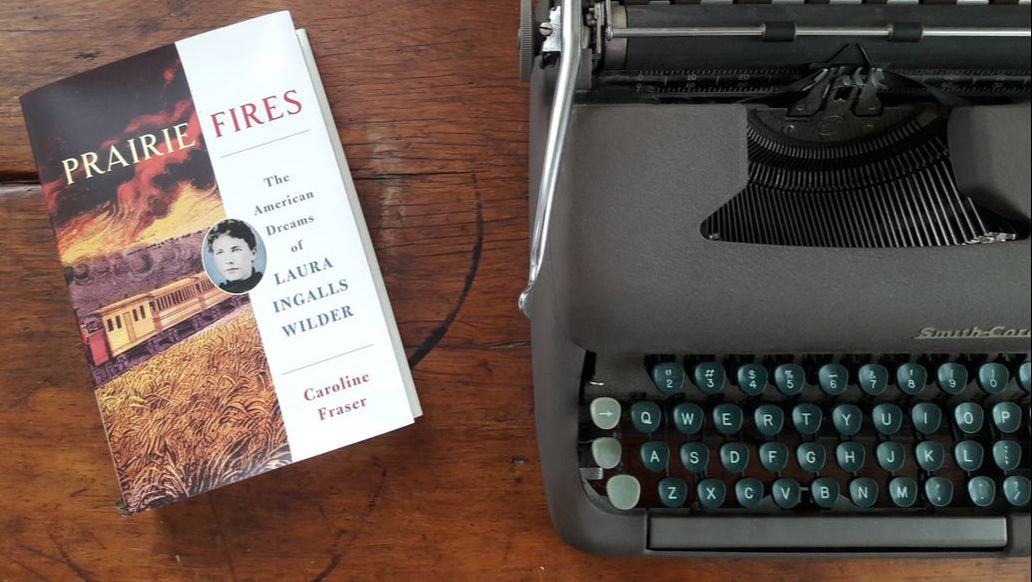

1/21/2018 1 Comment Reflections On: Prairie Fires“[A]s adults, we have come to see that her autobiographical novels were not only fictionalized but brilliantly edited, in a profound act of American myth-making and self-transformation.” Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder is the fascinating and sometimes frustrating biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder and, in almost equal measure, her daughter, Rose Lane Wilder. Written by Caroline Fraser, editor of the Library of America edition of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books, it is meticulously researched. That research is one of the book’s greatest strengths. But it is also the book’s greatest weakness. Wilder was born in 1867 and died just a few days after her 90th birthday in 1957. But Fraser does not confine her story to this timeframe. She starts instead with Edmund Ingalls, Wilder’s ancestor who arrived in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1628. Through Wilder’s family history, we are introduced Martha Ingalls Allen Carrier, the granddaughter of the Edmund Ingalls, who was accused of witchcraft and hanged at the height of the Salem witch trials in 1692. We also meet Samuel Ingalls, Wilder’s great grandfather, who married Margaret Delano, ancestor of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in the late 1700s. Finally, we meet Roger MacBride, who comes under Lane's spell in the 1940s, just as her political theology starts to coalesce into the foundation of the American Libertarian movement. In time, MacBride would become Lane’s surrogate son, political disciple (he was the presidential nominee of the Libertarian Party in the 1976 election), sole heir and keeper of the Wilder legacy. Fraser makes every effort to present Wilder’s story within a larger historical context. But at times, the history lessons interfere with or completely overshadow the underlying narrative. Wilder lived through both the Panic of 1893 and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. In both cases, Fraser gives a global and environmental context to these disasters. With regard to the Panic of 1893, Fraser writes:

She dives into global weather patterns, the futures market in Chicago, and the global shift from subsistence farming to a market economy that encourages monoculture and determines the price of agricultural products. Fraser places blame for the Panic of 1893 on market forces. But when it comes to the Dust Bowl, she places blame elsewhere:

Fraser’s vehement assertion that the blame for the Dust Bowl lies with small farmers combined with her failure to mention the role the United States government played in encouraging and rewarding those who settled and cultivated the Great Plains, speaks more to her personal biases as an environmentalist than to the complex assessment of responsibility for the Dust Bowl. Further, she barely touches upon the impact the Panic of 1893 and the Dust Bowl had on Wilder’s life, though it must have been considerable. In failing to address it, Fraser missed a tremendous opportunity to give a more personal account of what it was like to live through those events. Fraser’s strength is in revealing the false foundation of American mythology, which typically describes the frontier as an uninhabited wilderness. In Little House on the Prairie, Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote:

The implication, of course, is that native peoples were less than human. This belief is foundational to the philosophy of Manifest Destiny, which held that it was both inevitable and justifiable for settlers to expand across the North America and bring order to the wilderness. Wilder’s racism, at least in this context, is hardly surprising. Only by believing that White settlers were destined to bring order to the wilderness, and that native peoples were part of that wilderness, could Wilder justify her family’s decision to take advantage of the Homestead Act. In fact, to write the Little House books, which effectively reframed her childhood into an uplifting epic that would define much of America’s pioneer mythology, Wilder often had to turn a blind eye to her own reality. In truth, neither Wilder nor her beloved father, Charles Ingalls, always personified the values of “courage, self-reliance, independence, integrity and helpfulness” espoused in her books. Fraser is able to admit to Charles’s shortcomings, including running away from debts, endangering his family, and squatting on land he had no right to:

But Wilder’s own shortcomings are shared more reluctantly and are often accompanied by an explanation. In 1937, in a letter written to her daughter, Wilder rails against the New Deal. She confesses that those struggling financially, “are getting just what they deserve.” She shares her pride in the fact that she no longer needs to repair her old clothes because she has plenty of new ones. Yet, she refuses to give them away. Those who might benefit from her generosity, she complains, “would go on relief before they’d make them over.” Instead, Wilder lets her husband cut up her old clothes to braid into rag rugs. Fraser defends Wilder’s behavior, noting that over the course of her life, she had helped support her own family, helped send her sister to college, and was, in turn, often beholden to her own daughter. In explaining Wilder’s behavior, Fraser nearly apologizes for it:

Though reluctant to criticize Wilder, Fraser did not hesitate to condemn Lane. A prolific columnist with little regard for the truth, Lane wrote several serialized biographies of public figures, including Charlie Chaplin, Henry Ford, Herbert Hoover and Jack London, all of whom denounced Lane’s work as largely fabricated. According to Fraser:

As Lane got older, she began to publicly express anti-Semitic and racist views, lauding both Hitler and Mussolini. In 1936, she published Credo, a political screed published by the Saturday Evening Post that implied that the New Deal was dangerous to both Democracy and America. The essay set forth the philosophy of individual liberty and self-reliance that would ultimately become the foundation of the Libertarian Party. It was so popular that it was published as a pamphlet titled Give Me Liberty. Wilder kept copies on hand to send to her readers. Lane’s political views became more extreme as she got older, and seemed to match her erratic personality. Throughout her adult life, she would suffer bouts of severe depression followed by grand gestures that were frequently beyond her means; she would fly into a rage, berating those who knew her best, and then become desperately helpful in hopes of repairing the relationship. As her behavior and politics became more extreme, she disavowed many of her long-time friends. Although never offered as a possible explanation for her behavior, it was impossible for me to read about Lane’s life without thinking that she was struggling with mental illness. In many ways, I found her to be a tragic figure more than a contemptible one. And I found it striking that, no matter how extreme her political views became, Wilder always expressed her approval and agreement. While I enjoyed Prairie Fires, I was often frustrated by the narrative’s lack of focus. The relationship between Wilder and Lane was at the very heart of the Little House books, but it was only touched on tangentially. This, again, seemed like a missed opportunity. As is so often the case with mothers and daughters, Wilder and Lane had a complicated relationship. They were fiercely competitive, and yet completely dependent upon one another. They were creative collaborators, co-conspirators and confidants. They lifted each other up even as they tore each other down. I would have happily sacrificed some of the breadth of this meandering family history for a bit more depth. ★★★ Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, a biography by Caroline Fraser, published by Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company, in 2017. This book review is presented as part of my personal challenge to read and write a thoughtful review of at least 30 books in 2018. To learn more about this challenge, the books I have selected, and my imperfect rating system, click here.

1 Comment

|

|

|

The Scribbler's Journal

|

Contact |