Musings |

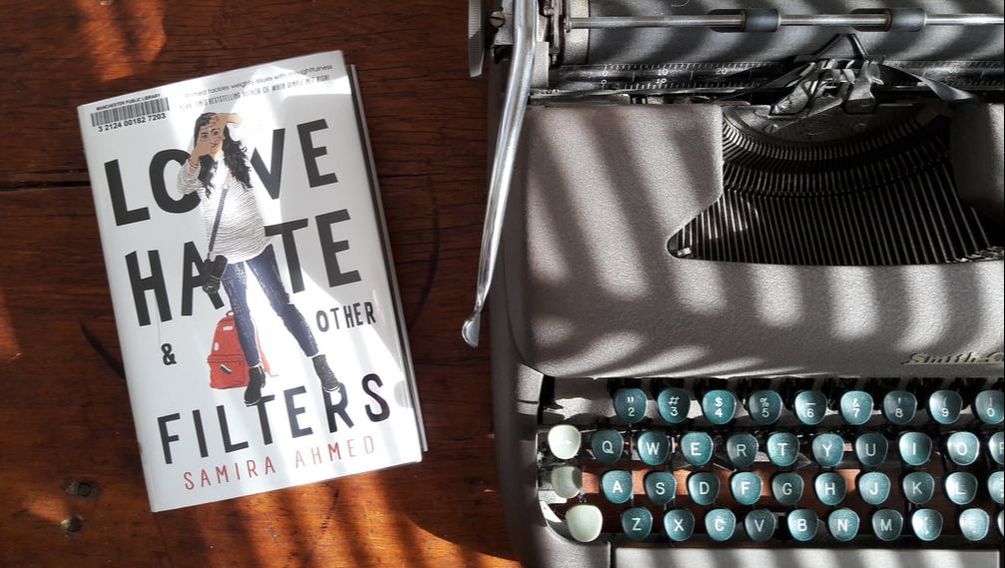

“I don’t know how to live the life I want and still be a good daughter.” Books have always been an important part of my life. When I have questions that I can’t answer, I turn to books. When I feel like the world is spinning out of control, I turn to books. Books are my constant companions and a source of both comfort and wisdom. I have always been able to pick up a book and see myself reflected in the characters. I took that privilege for granted. The publishing industry is slowly changing, thanks in part to a nonprofit organization called We Need Diverse Books. This grassroots effort brings together authors, agents, readers and publishers to promote children’s books, including middle grade and young adult, that reflect the lives of all young people. They advocate for more books that feature diverse characters so that all children can see themselves in the pages of a book. This is one of the reasons I read middle grade and young adult novels. There is more diversity in middle grade and young adult novels, and these books tend to tackle difficult subjects more directly and honestly than most adult fiction. Perhaps more importantly, when we look at a difficult issue through the eyes of a young person, we see it more clearly and are better able to understand and grapple with it. We set aside our desire to show that we already understand something and look at it from a different perspective. In Samira Ahmed’s debut young adult novel, Love, Hate & Other Filters, we meet seventeen-year-old Maya Aziz. A high school senior and the only child of Indian Muslim immigrants, Maya is, in many ways, a typical American teenager. She dreams of going to film school in New York City, has a crush on the quarterback of the football team, shares everything with her best friend and finds creative ways to rebel against her conservative parents. A second storyline is interspersed between chapters and we are offered a glimpse into the mind of a young man who drives an explosives-laden van into a federal building in Springfield, Illinois, killing more than one hundred people. As news of the attack breaks, schools throughout the state go on lockdown. And Maya is suddenly very conscious of her religious heritage:

According to early news reports, the suspected suicide bomber is an Egyptian named Kamal Aziz. Because he shares Maya’s last name, she and her family are suddenly viewed with suspicion.

Instead a racist classmate harasses Maya at school and someone throws a brick through a window at her parent’s dental practice, with a threat and their home address. In an effort to protect their daughter, Maya’s parents cancel social engagements and decide that Maya cannot attend New York University, but instead must go to college in Chicago, where she will still be nearby and can live with her aunt. We eventually learn that the terrorist was a white man named Ethan Branson. The original suspect, Egyptian national Kamal Aziz, was not the suicide bomber but a victim; a young man who was about to be sworn in as an American citizen. But Maya's parents are determined to keep their daughter close. Neither Maya nor her Aunt Hina, a hip graphic designer who lives by herself in a flat in downtown Chicago, can convince Maya’s parents to let Maya attend film school in New York City. Hina reminds her sister and brother-in-law of their decision to come to America against the wishes to their own parents. She also reminds them of her own journey, and their support for her decision not to marry or pursue a more traditional career but to focus on her art and design work. It is all to no avail. Maya must abide by her parents’ wishes or be disowned. The resolution is refreshingly realistic, but not terribly well developed. Throughout most of the book, Maya’s parents are somewhat flat, two-dimensional characters. Before their family is threatened they seem completely disengaged from their daughter’s life and we learn little about who they are and what motivates them. It is only when we learn a bit of their story from Hina that we realize they have the potential to be compelling characters. Equally disappointing is the sacrifice of two extraordinary characters, Maya’s aunt Hina and her best friend Violet, to Maya’s budding romance with Phil, the football team's star quarterback. Unfortunately, there is nothing particularly inspiring about this young romance, and the number of pages dedicated to this subplot far outweighs its significance. On the other hand, Ahmed’s decision to humanize the terrorist, to show us the abuse he suffered at the hands of his father, was both brilliant and heartbreaking. News coverage of attacks like the one depicted here often differs depending on the suspect’s skin color. People of color are labeled terrorists. We learn little about their background unless it supports the terrorist narrative. In contrast, when the terrorist is white, they are referred to as a lone wolf who is emotionally disturbed. If there is evidence of familial abuse, the media shares that information as well in an effort to support the lone wolf narrative. Like so many contemporary young adult writers, Ahmed doesn’t shy away from difficult topics. She helps us get to know an endearing character and then puts her in danger, helping us feel the fear, anger and disappointment a young Muslim woman experiences in response to Islamophobia. But she sacrifices several characters to accommodate a rather unoriginal teenage love story. And that sacrifice keeps the novel from reaching the level of depth and complexity that makes a story so enjoyable. ★★★ Love, Hate & Other Filters, a young adult novel by Samira Ahmed, published by Soho Teen, an imprint of Soho Press, in 2018. This book review is presented as part of my personal challenge to read and write a thoughtful review of at least 30 books in 2018. To learn more about this challenge, the books I have selected, and my imperfect rating system, click here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

|

The Scribbler's Journal

|

Contact |